The Possibility of Bridging Gaps in NCAA Sport Science

The landscape of collegiate athletics is constantly changing. Each year coaches need to take stock of their team, as new athletes join, some transfer, and others transition out. Coaching contracts depend on program performance, and outcomes can impact enrollment. Additionally, turn over of any kind can impact athletic departments. Institutional policies and incoming presidents can influence resource allocation. These are just a few examples that collegiate athletics are impacted by as seasons end. Usually, these are forward facing changes that occur, headline titles that we watch or read, especially when following Power 5 schools.

However, each athletic department has a team in the shadows. Individuals who devote their energy towards student-athlete development. This team in the shadows is usually made up of the various disciplines of sport science. In general, sport science is defined as multiple scientific disciplines coming together to understand and improve sport performance, ideally in a trans-disciplinary manner (Gleason et al., 2023). According to the authors of the definition there are nine roles that sport science disciplines partake in: education and knowledge tasks, performance enhancement programming, testing and profiling, problem solving, monitoring, research methods, technique evaluation, management, and training services. The disciplines are usually represented by athletic trainers, strength & conditioning coaches, sport psychologists, nutritionists, mental performance consultants, medical doctors, sometimes individuals who specialize in physiology, biomechanics, epidemiology, and motor control (Rimer et al., 2023). Now with athletic departments investing in wearable devices, another discipline that can be relied upon are statisticians (Sainani et al., 2021).

With all these sub-disciplines working toward a common goal in their own specialized ways, you wonder how much of it is actually done from a trans-disciplinary perspective. Meaning that challenges are overcome by shared responsibility across disciplines that span science and practice (DeWeese et al., 2023). Unfortunately, there is not much evidence in the literature providing concrete guidance on how a successful sport science department within collegiate sports looks like. Considering not all athletic departments across divisions work similarly. There currently is a lack evidence on how a well oiled sport science department is structured.

This question emerges from some anecdotal experience, but also from a significant amount of time spent researching sport psychology, and how sport psychology professionals navigate organizations. Additionally, there is a call for collaboration between psychologists who specialize in sport with mental performance consultants (McHenry et al., 2022). This is because it is not uncommon for athletic departments to hire one person for mental health support and mental performance work. The current landscape of that across 253 DI athletic departments have a provider to client ratio on anywhere between 1:200 to 1:800 (Jones et al., 2022). Even on the lower end of that spectrum, having one person serving as an athletic trainer and a strength coach for 200 student-athletes is an unimaginable of a task. This led be to consider organizational structures around student-athlete welfare. Leading me to sport science encompassing all sub-disciplines of athlete health and performance.

It was disappointing to find out the lack of evidence around the organizational structure of a sport science department within the NCAA. In a collegiate system like in the USA, which is one of a kind in the world. There is potential to cultivate a depth and breadth in the literature about best practices of institutions creating sport science departments within their athletic system. There is an opportunity if disciplinary boundaries are willing to be breached. Therefore, the purpose of this article is threefold: (1) explore potential structures, (2) examine characteristics of success, and (3) recommend roles that can lead such departments.

The Structure of Sport Science Departments

A brief review of what a sport science department may look like was provided by Hornsby and colleagues (2021), who suggested three models to consider: (1) athletic departments partner with academic departments, using the expertise of the faculty within an institution to spearhead athletic research, education, and innovation; (2) athletic departments can hire in-house sport scientists across disciplines, providing the student-athletes with greater accessibility of service; or (3) existing athletic department staff oversee sport science processes. These all seem like tangible approaches, but I was wondering how are these implemented and what is the quality of functioning. This paper provided three examples of the integration of sport science departments within the NCAA, but what is the structural design on how they operate.

Before I continue, I want to be sensitive to the fact that every single athletic department is unique. Not every athletic department has the same organizational structure when it comes to sport science. That is probably true across all conferences and divisions. I also speak from a young professional perspective (potential naiveté). Anecdotally, working in six athletic departments across all divisions, each one operated differently than the next. However, one theme stood out across them all. Sport science disciplines operated alone. Siloed off, focusing on it’s own programming and evaluation.

As I reflected on the silo phenomenon across disciplines, I wanted to see if there is anything published on sport science models. Rimer and colleagues (2023) comprehensive integration paper, encouraging the next generation of best practice. They are at least encouraging a model. The central thesis of a comprehensive integration approach is combining every available resource to establish unprecedented health and performance support for student-athletes. The key components to do that is to integrate services across sport science disciplines (i.e., strength & conditioning, mental health, athletic training, mental performance, nutrition), conduct research through program evaluation to assess and monitor services and outcomes, facilitate growth and development through education, and provide space for innovation (Rimer et al., 2023). Applying a comprehensive integration approach sounds nice on paper, but implementing it seems complex. Can’t wait to read a case study on it!

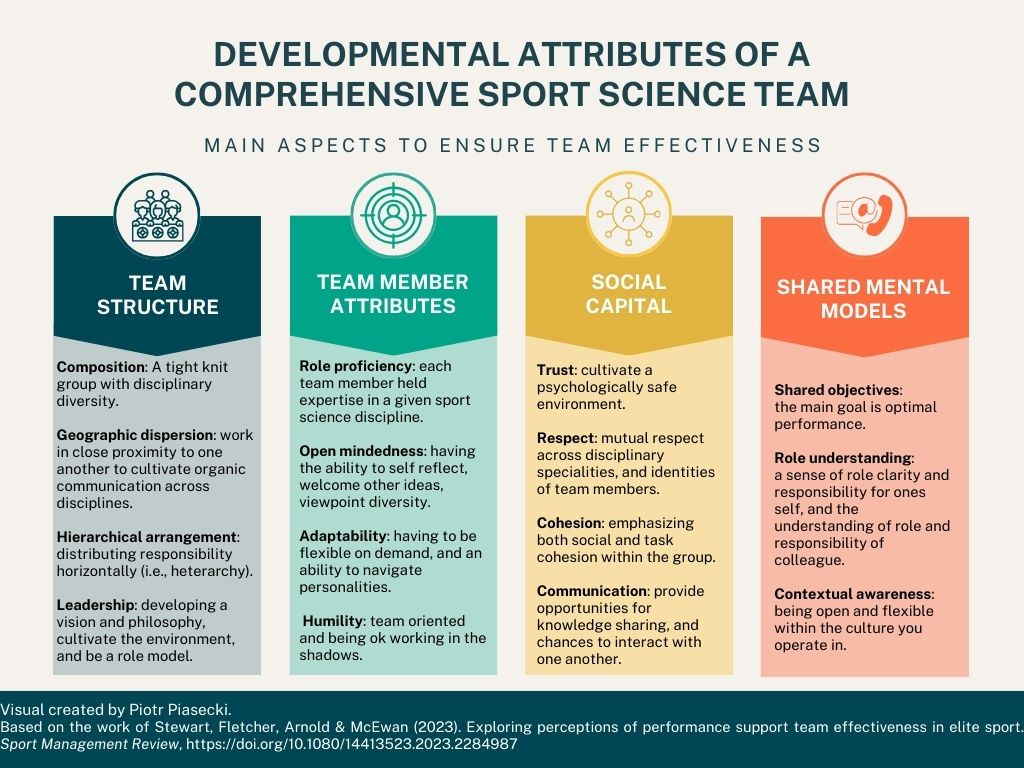

Applying any type of an approach for collaborating across sub-disciplines of sport science, examining attributes of success are important. Stewart and colleagues (2023) published a qualitative study examining team effectiveness within integrated sport science departments, however not within an NCAA context. The sample included various performance contexts (English Premier League, Formula 1, and Olympic sports). The study concluded that four major themes impacted the effectiveness of the sport science department. Find them in Figure 1.

The above characteristics based on integrated sport science teams provide us with a roadmap as to what is required to operate an effective team. However, it begs the question, how are these created? Who is responsible for creating them? Stakeholders? Practitioners of a particular sport science discipline?

This is where the concept of structural design plays a role. Structural design is the essence of an organization. It communicates roles, distribution of resources, and lines of communication across departments. A study examining the structural design of 86 senior level administrators from NCAA institutions found that having an enabling structure showed greater athletic achievement (Cunningham and Rivera, 2001). Enabling structure is defined as a decentralized decision making structure, allowing for members across hierarchical lines to make decisions. This decentralized decision making structure would fit well into a sport science department where each discipline has its own level of specialization and expertise toward human optimization.

Following the thread of decentralized structures, a sport science department working towards comprehensive integration can look towards the Department of Methodology (DoM) model (Otte et al., 2022). A DoM is

“an organizational entity, conceptualized as a complex adaptive system, integrating the work of coaches and sub-discipline specialists into a unified athlete development and performance preparation team. A DoM supports coaches and support staff in functioning as a cohesive and integrated unit (department), based on shared scientific concepts and principles of practice to collectively design environments for athlete development and performance preparation (methodology)” (p. 4; Otte et al., 2022).

A DoM moves beyond a sport science department and integrates all organizational players. It’s person is required to work beyond their disciplinary boundaries and be open minded by what other disciplines have to offer, collaborating with one another to optimize the individual/team. This idea of having a DoM as vehicle for comprehensive integration sounds like poetry. I say that because Figure 1 speaks about what type of characteristics potentially need to fall into place for fluidity to occur. Furthermore, Otte and colleagues (2022) discuss the importance of working in a heterarchical system, where the organizational players can move across disciplinary boundaries to enrich developmental approaches. In other words an enabling structure discussed in structural design.

Continuing to look beyond literature published on collegiate sport. A study examining four European sport science research centers that rely on collaboration (Camy et al., 2017) investigated four dimensions: (1) scientific, (2) organizational, (3) academic, and (4) societal. Focusing on the organizational dimension, Camy and colleagues (2017) examined each sport science centers’ structural design, based on the daily lives of its members including governance, spatial organization, equipment, relationships between disciplines, policy and practices, career management, and informal rules and regulations. A few of the main findings included the importance of collective proximity, allowing for informal interactions across disciplines. I am bias regarding the discipline, but this is something to consider when introducing psychology into an athletic department, ideally you want to be integrated into the structure of athletics. In one of the cases, the sport science center went to the extent of housing two people with different disciplinary training backgrounds in the same office to cultivate collaboration. Camy and colleagues also stress the importance of organizational culture:

“Organizational form is an essential element where the practice of interdisciplinarity is founded. It requires a collective project taken up my all members, and necessitates the construction of a shared world where individual interests find a space for expression without weighing heavily on the collective interest” (p. 8).

A big piece to such a collective project, whether you align with the DoM or the comprehensive integration or some other approach, it all depends on stakeholders. The executives within an athletic department. It can only exist sustainably if industries and athletic department stakeholders (i.e., executive administrators, funders) believe there to be a space for such collaboration for the greater development of the student-athlete. I believe it also depends who is leading such an initiative, therefore the need to explore sport science leadership.

Sport Science Leadership

Both the comprehensive integration approach and the DoM don’t provide much on who will lead such a sport science department. Although, the comprehensive integration approach shares a checklist for athletic departments to use when initiating the process in creating a sport science department and recommend a generalist to be the first to lead such a role (Rimer et al., 2023). Aside from that, no evidence is provided to direct administration towards who has the skills to step into such a position. However, Stewart et al., (2023) discuss the importance of leadership to first develop a vision for said department and set out to create a philosophy and values around it. One must cultivate a collaborative environment, welcoming each discipline, and valuing each person for the richness they bring with their expertise, a shared world. It also must be understood to model what one preaches. This is a tried and true attribute of any leader.

According to DeWeese and colleagues (2023), who mention the lack of clarity throughout the literature of a sport science directors identity, state that this person needs to be an intrapreneur. Someone who is capable of skillfully navigating systems, capable of filtering relevant information, managing tactics towards improvement and innovation, all while working in relationship with disciplinary experts. The authors go on to share 14 anecdotal responsibilities that a director of a sport science department may face (see DeWeese et al., 2023). Moreover, they mention requirements that a person should meet when stepping into such a role:

Expertise —> knowledge in at least 2 disciplines and a strong working understanding of others.

Interpersonal & communication skills —> ability to effectively communicate (i.e., informally-formally, email, text, chat). Important for developing trust and buy-in.

Career experience —> around 7 to 10 years of experience serving in a leadership capacity as a discipline specific director.

Historical achievement —> resume of implementing measurable performance improvements.

Strategic process planning —> content specific curriculum development, intervention implementation, and periodization.

Education —> Terminal degree within the sport science leader’s academic field.

These are some heavy requirements, but necessary when having to lead experts across disciplines. Additionally, the authors conclude with eight anecdotal attributes of a director (see DeWeese et al., 2023). I hope this paper encourages future research to potentially examine what they have written or at least get researchers interested in investigating the topic further.

What does a potential leadership position look like for a sport science department. I believe it would fit well for an individual who has expertise in sport/organizational psychology to be considered for such a role. Wagstaff and Quartiroli (2023) propose a Head of Performance Environment (HOPE) to lead a trans-disciplinary team. They mention how individuals who have an expertise in the sport science sub-discipline of psychology traditionally provide support to systems in various complex ways. The diversity of roles psychologists can manage involve being a strong negotiator of difficult social dynamics, navigator across various complex social interactions, and an architect of team culture (Wagstaff & Quartiroli, 2023). This actually ties in well with what DeWeese and colleagues (2023) outline regarding ideal attributes of a leadership role. Additionally, with the plethora of research on group dynamics in both organizational psychology and sport psychology, an expert in this literature would be a strong candidate for a HOPE in a comprehensive integrated system, DoM, or any type of sport science department.

According to Wagstaff and Quartiroli (2023), success for a leader in sport science department would include taking a systems-led approach. Such an approach is

“characterized by processes for collective awareness raising and shared understanding through formal and informal sense making processes, the development of proactive initiatives that promote socially just and empathic appreciation of others, psychological flexibility, and co-creation and creative-problem solving” (p. 4).

With the leadership of a HOPE within these complex sport science departments, there is literal hope for the development of athletes. Especially when thinking about a leader who is psychologically informed, this speaks to the concern of student-athletes, their mental health. Not only with athletes, but also across athletic department administration. A few general recommendations regarding responsibilities of a HOPE found in Figure 2.

These responsibilities align with the director paper DeWeese and colleagues (2023) published. Interestingly enough, this is evidence that sport science disciplines overlap, where one paper is written in a strength & conditioning journal, and the other in a applied sport psychology one. It is wonderful to see similar recommendations being made. This already is an example of bridging the gap between sport science disciplines, which in turn provides HOPE for athletic departments.

To conclude, I’m aware that there are probably plenty of sport science departments out there that have wonderful systems at work, who not always include all sub-disciplines, but I believe that this integration will be happening and continue to happen. Just take a look at the published materials in this text, all in the past few years. Additionally, practitioners in athletic departments need to be encouraged to conduct research and/or participate in research for evidence to exist on how to navigate disciplines of sport science in collegiate sport. The embodiment of a scientist-practitioner not only in applied work, but also in knowledge creation is needed.

References

Camy, J., Fargier, P., Perrin, C., & Belli, A. (2017). Forms of interdisciplinarity in four sport science research centres in Europe. European journal of sport science, 17(1), 30-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2016.1218551

Cunningham, G. B., & Rivera, C. A. (2001). Structural designs within American intercollegiate athletic departments. The International Journal of organizational analysis, 9(4), 369-390. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028941

DeWeese, B. H., Hamilton, D. K., Huls, S., Peterson, B. J., Rath, T., & Althoff, A. (2023). Clarifying high performance and the role, responsibilities, and requisite attributes of the high-performance director in American professional sport. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 45(4), 429-438. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/abstract/2023/08000/clarifying_high_performance_and_the_role,.4.aspx

Gleason, B. H., Suchomel, T. J., Brewer, C., McMahon, E. L., Lis, R. P., & Stone, M. H. (2022). Defining the sport scientist. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 10-1519. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/abstract/2024/02000/defining_the_sport_scientist.2.aspx

Hornsby, W. G., Gleason, B. H., Dieffenbach, K. Brewer, C., & Stone, M. H. (2021). Exploring the positioning of sport science programs within intercollegiate athletics. NSCA Coach, 8(3), 6-11.

Jones, M., Zakrajsek, R., & Eckenrod, M. (2022). Mental Performance and Mental Health Services in NCAA DI Athletic Departments. Journal for Advancing Sport Psychology in Research, 2(1), 4-18. https://doi.org/10.55743/0000010

Otte, F., Rothwell, M., & Davids, K. (2022). Big picture transdisciplinary practice-extending key ideas of a Department of Methodology towards a wider ecological view of practitioner-scientist integration. Sports Coaching Review, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2022.2124001

McHenry, L. K., Beasley, L., Zakrajsek, R. A., & Hardin, R. (2022). Mental performance and mental health services in sport: A call for interprofessional competence and collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(4), 520-528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1963218

Rimer, E., Petway, A., Jones, P., Schultz, R., Hayes, B., Suchomel, T. J., ... & Ivey, P. (2024). Building comprehensive integration of health and performance support through sport science. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 46(1), 55-68. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/abstract/2024/02000/building_comprehensive_integration_of_health_and.6.aspx

Sainani, K. L., Borg, D. N., Caldwell, A. R., Butson, M. L., Tenan, M. S., Vickers, A. J., ... & Bargary, N. (2020). Call to increase statistical collaboration in sports science, sport and exercise medicine and sports physiotherapy. British journal of sports medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102607

Stewart, P., Fletcher, D., Arnold, R., & McEwan, D. (2023). Exploring perceptions of performance support team effectiveness in elite sport. Sport Management Review, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2023.2284987

Wagstaff, C. R., & Quartiroli, A. (2023). A Systems-Led Approach to Developing Psychologically Informed Environments. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2023.2215715